|

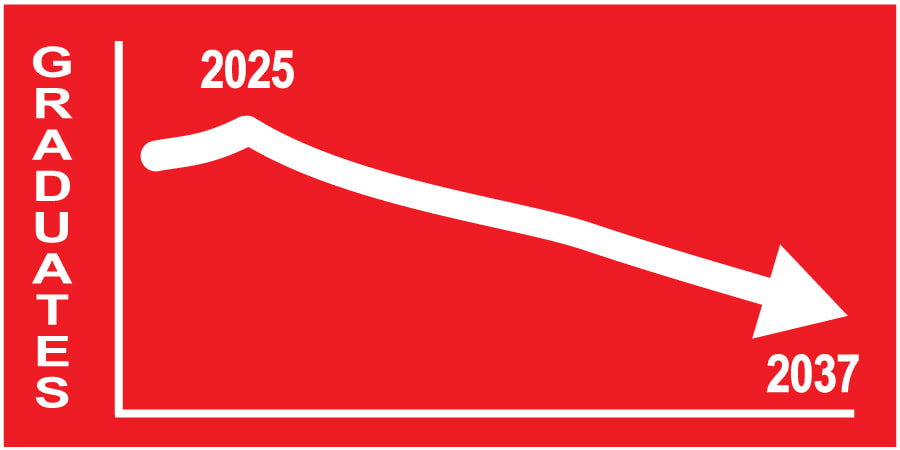

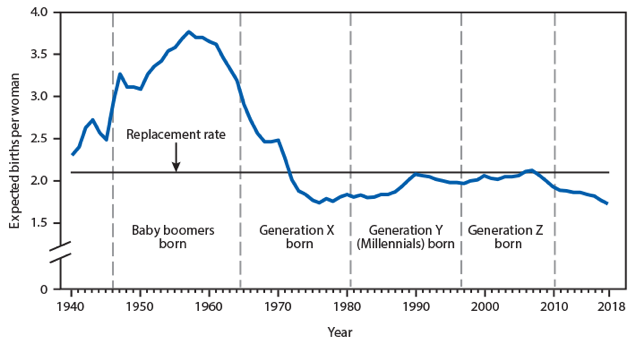

For most colleges and universities, the past year has been full of obstacles and challenges the likes of which they have never seen, but it may pale in comparison to the demographic shifts expected to affect many of them in the next 10-15 years. U.S. high schools have produced a steadily increasing supply of graduates since an annual low of 2.4 million in 1995, but this population is expected to peak in the next few years at 3.9 million before declining to levels seen in the early 2010s. While this decrease in potential students may threaten some alma maters, the shift in power from colleges to applicants will benefit students applying in the coming years. Today’s CrisisFor many schools, the imbalance is already apparent, and students applying in the next few years will likely benefit from current trends driven by the pandemic, which has dampened demand for and accessibility to higher education for many students. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, enrollment at U.S. colleges dropped to the lowest level in almost twenty years in October, only 62% of high school graduates from the Class of 2020 were enrolled in a post-secondary school, as the many effects of the pandemic reduced the number of students applying to and enrolled in college. The National Student Clearinghouse reported similar findings with undergraduate enrollment down nearly 6% year-over-year at its member institutions. According to National Association of College and University Business Officers, colleges are adjusting how they achieve enrollment numbers in the face of this drop in demand, “Nearly two-thirds reported employing new recruitment methods, about 62 percent reported using new retention strategies, more than half went test-optional, and about half offered new financial aid strategies.” Still, many schools are reporting open slots in May, with the National Association for College Admissions Counseling’s database showing more than 420 U.S. schools with available space right now. For students applying this fall, many factors are in their favor, so they should not be afraid to ask what the school can do to lower their tuition and support their career development. Long-Term Declines Will Force Schools to ChangeSource: Centers for Disease Control Long term, the decline in student populations will be driven by the declining birthrate in the United States, which dropped to 1.73 children per mother in 2018, well below the 2.1 rate necessary to maintain population levels. This is down from its most recent peak in 2006, after which the economic recession forced many families to delay having children. Translated out, student populations should start to decline proportionally for the high school class of 2025 and beyond. That is the incoming freshman class. Colleges have already seen declines in attendees of more than 2.6 million students (13 percent) over the last decade, so the further drop of 10-15 percent anticipated during the next decade will only exacerbate the situation. The shrinking applicant pool will force colleges to re-invent their offerings, recruitment, and value propositions in order to appeal to more students and to work harder to keep the ones who do register for freshman year. The pandemic has accelerated these changes on many campuses, with schools adopting new approaches on the fly such as virtual visits, outreach to new geographic areas, and reducing their degree offerings to focus on their best or most in-demand programs. Schools can also improve their outcomes by focusing on retention of existing students and on helping students with a path to employment after graduation, adding value to the degree. Will Lower Demand Lower Costs?Another potential upside for students is that the lower demand may finally force schools to reign in their unrealistic annual cost increases, which have been at twice the pace of inflation since the 1980s. Many schools took steps along these line during the pandemic due to pressure from students and parents. According to the College Board, “(a)verage tuition and fees increased by 1.1% for in-state students at public four-year institutions, 1.9% for in-district students at public two-year colleges, and 2.1% for students at private nonprofit four-year institutions. The 1.1% and 2.1% are the lowest one-year percentage increases for public four-year and private nonprofit four-year sectors in the last three decades.” While we do not see the list price of most colleges dropping significantly, we do anticipate costs to flatline or show little growth in the years ahead as schools compete for fewer students. Most importantly, the actual cost paid by the students, versus the sticker price in the school brochure, is also likely to go down, as the average discount rate has been increasing, up to 54% for first-year undergrads at private colleges in 2020 according to the National Association of College and University Business Officers. Key Takeaways

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorAnn Derryberry Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

Telephone |

© 2024 Everest Tutors & Test Prep | All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed